- Home

- Schlissel, Lillian

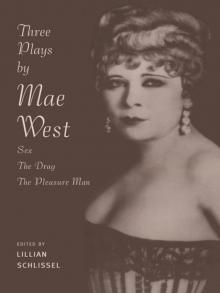

Three Plays by Mae West

Three Plays by Mae West Read online

THREE

PLAYS

by

MAE

WEST

Shubert Aichive

Page from Playbill of Sex, 1926.

THREE

PLAYS

by

MAE

WEST

Sex

The Drag

The Pleasure Man

Edited by

Lillian Schlisse

Published in 1997 by

Routledge

270 Madison Ave,

New York NY 10016

Transferred to Digital Printing 2010

Introduction and notes copyright O 1997 by Lillian Schlissel.

Sex, The Drag, and The Pleasure Man copyright O 1997 by the Estate of Mae

West. All inquiries concerning performance rights to these plays may be

addressed to the Roger Richman Agency, Inc., 9777 Wilshire Blvd., Beverly

Hills. CA 90212.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or

utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now

known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in

any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing

from the publishers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

West, Mae.

[Plays. Selections.]

Three plays by Mae West : Sex, The drag, The pleasure man / edited

by Lillian Schlissel.

p. cm.

Previously unpublished plays.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-415-90932-5 (hb).--ISBN 0-415-90933-3 (pb)

1. Women--Social conditions--Drama. 2. Sex customs--Drama.

I. Schlissel, Lillian. 11. Title.

PS3545.E8332A6 19976

812'.52--dc21 97-24425

Publisher's Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint

but points out that some imperfections in the original may be apparent.

CONTENTS

Introduction by Lillian Schlissel

Sex: A Comedy Drama (1926)

The Drag: A Homosexual Comedy In Three Acts (1927)

The Pleasure Man: A Comedy Drama (1928)

The Case Against Mae West

INTRODUCTION BY LILLIAN SCHLISSEL

Mae West’s plays, Sex, The Drag, and The Pleasure Man are published here for the first time. Sex, which opened at Daly’s 63rd Street Theatre just north of Broadway in 1926, gave West her first starring role in the theatre and marked the beginning of one of the most extraordinary American careers.

Mae West began writing as a teenager on the vaudeville circuit She wrote encores to her songs because she was so sure audiences would call her back. She wrote night club acts, two novels, scripts for her Hollywood films, and, of course, her stage plays. She was a writer as much as a performer, and the likelihood is that if she had not written her own material, there would have been no stellar career.

The Mae West scripts are part of the Manuscript Collection of the Library of Congress—The Ruby Ring (1921), The Hussy (1922), The Chick (1924), Sex (1926), The Drug (1927), The Pleasure Man (1928), Diamond Lil (first and second versions, 1928, 1964), Frisco Kate (1930) and The Constant Sinner (stage version of the novel Babe Gordon, 1931), Catherine Was Great (1944), Come On Over (also called Embassy Row), 1946), and Sextette (first and second versions, 1952 and 1961). Sex and The Drag were copyrighted under the pseudonym jane Mast, but it was an open secret that the plays were Mae West’s.

She was never an original writer. Critics accused her, as they had accused Brecht, of “pirating, plagiarizing, shamelessly appropriating.”1 Writers who claimed she had stolen their work often pursued her in the courts, but she defended her claim. Once she had “borrowed” a script, she was convinced that even the original idea had always been hers.

On the stage, Mae West played the “tough girl.” In Sex, her self- congratulatory bravado and cocky invitation to sexual adventure carried the play, but unlike other “fallen women” of the day, the sexuality she displayed was closer to comedy than to passion.

Critics who applauded her smart-mouthed quips sometimes suggested that the flamboyant sexuality that became her trademark was a disguise. No real woman could be so brazen, so self-contained, or so funny. That a woman who played the bawd for half a century should have stirred debate about her sexual identity is part of the intrigue that has surrounded Mae West’s style and career.

The “gay plays,” The Drag and The Pleasure Man, are at the heart of the question. Readers have searched the yellowing pages of the scripts in the Library of Congress as if the leaves were written in some ancient hieroglyphic that would reveal a secret if rightly deciphered. The trouble is that The Drag and The Pleasure Man heighten questions of sexual transformations; they do not resolve them. For one thing, the scripts refute West’s statement that she wrote because she needed material for the stage. She never appeared in The Drag, and she never appeared in The Pleasure Man. Each play was meant to be performed by a company of gay actors while she starred in the heterosexual play grounds of Sex and then Diamond Lil. Yet she was obsessed with the gay plays, revising and rewriting them through the 1970s, hoping to turn them into films.

The publication of Sex, The Drag, and The Pleasure Man places Mae West’s work beside contemporary plays like Eugene O’Neill’s Anna Christie (1922), Oscar Hammerstein’s Showboat (1927). and Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur’s Front Page (1929). Sometimes similarities are striking—Brecht’s Threepenny Opera opened in Berlin in 1928. only a few weeks before Diamond Lil opened in New York. Lotte Lenya’s role as the Whore Jenny bears close resemblance to Mae West’s Margy LaMont in Sex and to her role in Diamond Lil. After all, it was Brecht who wrote “in our day sex undeniably belongs to the realm of comedy.”2

The vulgarity of Mae West plays was meant to disrupt standards of propriety. The speech was intended to sow the seeds of revolution. No victory is so triumphant as a dirty word spoken in public; no guerrilla warfare so subversive as the moment when an audience, in spite of its best intentions, laughs at a really low joke. West’s assault on the standards of decency would be played out in the arena of sexual license, but her enduring significance is her comedy where words are weapons and wit is the arsenal of attack.

The current interest in Mae West—the new essays in cinema journals, the new critical studies—attests to the fact that we are catching up with ideas that interested her, with her belief that virtue is unconnected to sex, and that sexual identity ranges over human experience from heterosexuality, to bisexuality, to homosexuality. In the plays, ethical choices are constructed out of sexual identity, but sexual identity is unstable.

For me, this book goes back twenty years, to 1974 when I first read the plays in the Library of Congress and pursued the possibility of getting them into print. My thanks to the Roger Richman Agency for its permission to publish these uncut scripts, and to Routledge, which over the past five years has patiently waited until legal matters were cleared. For readers who have long believed Mae West is an underrated figure, these plays provide the basis for new assessments of her impact on American theatre and letters.

Born in 1893, Mae West was the daughter of Matilda and Jack West. Her mother was a “refined” Austrian corset model and her father a small-time boxer known in Brooklyn as Battlin’ Jack. She was a streetwise kid who grew up in Bushwick, a neighborhood where the dialect, like Cockney, was a life-long affliction. Her mother put her on the stage when she was six. West played Little Eva in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and Sis Hopkins in Huck Finn, and a

lways managed to make her lacetrimmed bloomers more important than her lines.

Although she rarely acknowledged his influence, Jack West was important in her life. He took her to the fights and taught her the boxer’s regimen of weightlifing; by the time she was a teenager, she was all strut and swagger, moving around the stage like a bantam weight fighter.

She went out on the road when she was sixteen and teamed up with a hoofer billed as Frank Wallace, born Frank Szatkus, son of a Lithuanian tailor. They were married in Milwaukee on April 11, 1911. But like Fanny Brice, whose marriage to a Springfield barber ended abruptly, Mae ditched Wallace when she got back to New York in June.

She spent the summer in Coney Island saloons, with Jimmy Durante, who worked at Diamond Tony’s on the boardwalk, and with songwriter Ray Walker, who played piano all night while Dutch Schultz held a gun to his head. Walker wrote a song for her called “Good night Nurse” (words by Thomas Gray). It was the first piece of sheet music with her photograph on the cover. She was an ordinary girl, a pretty brunette.

In 1911, she was getting small parts in musical revues, mostly through young men she dated on their way to becoming writers and producers. She was in A la Broadway and in Vera Violetta. A New York Times reviewer noticed an unknown “with a snappy way of singing and dancing,” but Sime Silverman of Variety wondered if this “tough soubret” out of Brooklyn, who danced the Turkey (also the Fox Trot, the Monkey Rag, the Grizzly Bear, and the Shimmy) was not “just a bit too coarse for this $2.00 audience.”3

She studied “big time” performers like Eva Tanguay, who sang “I Don’t Care.” She imitated the black vaudevillian Bert Williams, and listened to the fast-paced jokes of Jay Brennan and Bert Savoy. “In an era that did not allow recognition of the homosexual, let alone admis sion of being one, Bert was an outspoken example, yet so funny about it that nobody seemed to mind.” Savoy played cheeky dames named Margie and Maude, gossipy secretaries and beauticians, party girls, and flirts. He wore a red wig and enormous picture hats. His camp humor played to audiences from New York to the Klondike. By 1920 he was the darling of the critics and Vanity Fair called him “The reigning Ziegfield beauty.” Savoy’s one-liners were razor sharp. The minister asks at choir practice, “Don’t you know the Ten Commandments?” and Margie snaps, “No, but if you’ll hum a bit for me, I think I can play the tune.” Off stage, Savoy was just as outrageous. Stopping in front of Saks Fifth Avenue, he told friends, “It’s just too much. I don’t care if he is building it for me…. I’ll never live in it!”4 Mae West onstage probably owed more to Bert Savoy than to any woman in the theatre before 1920.5

After 1919 West was playing in a string of revues. She was Mayme Dean of Hoboken in Sometime, and Shifty Liz in The Mimic World (1921). She was flashy and pretty, but her streetsmart manner offended some audiences, and Variety kept warning her to “tame down” her stage presence or she would “hop out of vaudeville into burlesque.”6 She was always writing her own material, impatient for the break that would make her a star. She wrote a night club act where Harry Richman did a kind of male striptease while she sang “Frankie and Johnnie”—in a version she had learned from JoJo the Dog-Faced Boy at Diamond Tony’s in Coney Island. The act took Richman and West to the Palace Theatre, but Richman quit and went to work with Nora Bayes, while West settled into a period with little work.

The big break did not come, and though she denied it all her life, film historian Jon Tuska believes that she went to work in burlesque. The Billboard Index between 1922 and 1925 includes notice of a performer spelling her name “May West” who appeared in Playmates, Girls from the Follies, Round the Town, French Models, Lena Daly and Her Tobasco Company, and Snap It Up.”7

Those years might have shaken the confidence of any actor, but West was indomitable. She apprenticed herself to a new craft and turned herself into a playwright. Her first script was called The Ruby Ring (1921), which set her at the center of the play as a “jazz baby.” Jim Timony, a lawyer and friend of the family, hired a young screen writer, Adeline Leitzbach, to work with her, and together West and Leitzbach wrote The Hussy (1922). The plays were practice pieces in which Mae West wrote of herself as the dazzling heroine so beautiful no man could resist her, so virtuous that her dancing and wisecracks could be forgiven, and so wise she’d find a rich husband at the end of the story

Leitzbach and other young women were moving into the business of the theatre, writing for vaudeville and for film. Anita Loos honed her skills on Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, which opened in 1926. Blues singers Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith wrote almost a third of their own lyrics. Blanche Merrill, still in high school, began writing skits for Fanny Brice and soon became her principal writer. Dorothy Parker worked for Vogue and Vanity Fair.

Elinor Glyn wrote pulp fiction romance, a new genre that led some wags to snicker, “Would you like to sin/ With Elinor Glyn/ On a tiger skin/ Or would you prefer/ To err with her/ On some other fur?”8 Hollywood paid Glyn $50,000 in 1925 to endorse Clara Bow, a twenty-one-year-old redhead, as the “IT” girl. Dorothy Parker sneered, “’IT/ hell, she had Those.” With “those” and no experience at all, Clara Bow earned $1000 a week, starring in movies as fast as the studios could turn them out.9

Clara Bow arrived in New York in 1925 to make Dancing Mothers at Paramount’s Astoria studio. Mae West was thirty-one. She had been in vaudeville and burlesque for twenty-five years, and she could see no reason she should not generate the same excitement on the stage as Clara Bow on the screen. But there was one difference. In her early films, Clara Bow did not speak. Mae West, on the other hand, was about to launch a frontal assault on verbal taboos and turn the Broadway stage into a battlefield.

Timony bought a script called Following the Fleet for $300 from Jack Byrne of East Orange, New Jersey (throwing in another $10 for a hat for the playwright’s wife). Following the Fleet was a third-rate sex play set in a Montreal brothel. Business is interrupted by the arrival of a “society lady” drugged and dumped by a blackmailing pimp. A prostitute named Margy LaMont tries to help Clara escape, but Clara accuses Margy of stealing her jewelry. The scene shifts to Trinidad, where—as befits melodrama—Clara’s son falls in love with Margy. Since he cannot marry a fallen woman, he returns to his mother and Margy goes back to the brothel.

Clara Bow had just finished a movie called The Fleet’s In, in which she played a taxi dancer, and Mae West was certain she could do better. She began by changing the ending of her play. In her version, the prostitute dumps Clara’s son, chooses her sailor sweetheart, and they dance off together to start a new life in Australia. As the final curtain comes down, the hooker is heroine. Then Mae West retitled the play with a single word—Sex. She said later that Edward Elsner, the director, kept talking about how the play exuded “Sex, low sex. The way he said it, it sounded like the best kind.”10

Considering that her credentials were modest, that she produced the play with money she borrowed from her mother, the success of Sex was astonishing. In writing of a hooker and a happy ending, Mae West challenged Broadway rules. Charles MacArthur and Clarence Randolph adapted Somerset Maugham’s Rain in 1922. The production starred Jeanne Eagels as the tough-talking Sadie Thompson, and the scene was the distant landscape of a Pacific island, but nothing in the stage version altered the bleak ending Maugham had written for the original story. Jack McClellan’s play The Half Caste was another tale of “Love and Sacrifice on the islands of Forgotten Men in Samoa,” and White Cargo (1924), which featured Annette Margulies as Tondalayo, the part that would make Hedy Lamarr a star in film, was similarly catastrophic at the final curtain.

Broadway indulged itself in scores of “sex plays,” all of them obedient to the unwritten rule that prescribed ruin for fallen women. John Cotton’s Shanghai Gesture opened at the Martin Beck Theatre in 1926, with Florence Reed as Mother Goddam, an oriental madam who ruled over an elaborate bordello with rooms called the Gallery of Laughing Dolls, the Little Room of the Great Cat, and the Green Stairway of the

Angry Dragon. Mother Goddam sacrifices her own child, a hopeless drug addict, for revenge. Shanghai Gesture was a bordello suffocated by gloom and doom and the punishment of sin.

Lulu Belle, by Charles MacArthur and Edward Sheldon, opened in February 1926 under the “personal direction of David Belasco.” Lulu was played by Lenore Ulric, a daughter of Minnesota who had made a career of playing passionate, dark-skinned women. She was a Spanish senorita, she was the “Saffron Chinese” Lien Wha in Tiger Rose, she was Carmen, and finally she was the notorious black prostitute Lulu Belle. She couldn’t know that Humphrey Bogart would remember her in 1943 in the film Sahara, naming his desert tank the Lulu Belle.

In Sex Mae West broke with Broadway moralities and made sin a domestic product. The scenes in the brothel were set not in the tropics but in Montreal, and although the second act moved to Trinidad, the last act brought the story back to Connecticut. And as Margy LaMont, Mae West was unmistakably a New Yorker who talked about a moniker, a joint, a dump, a jane, being gypped, giving someone the gate, planting a body under the daisies. She would “chuck the bugger” and “bankroll a kid.” Margy talked about sugar daddies and dames, about dolling up, about croaking a guy, and putting on the ritz, about paying the freight, about dirty rats, and dirty liars, and “dirty charity.” Margy’s goodbye is “blow, bum, blow.” When Dashiell Hammett elevated the “private eye” to an American hero in The Maltese Falcon (1929), when Sam Spade talked about suckers and chumps, about “taking the fall,” and putting in “the fix“—all that language had been set in place by Mae West. West’s language came out of the speakeasies, and the jokes she used were the familiar routines of burlesque. Critics might pretend outrage, but audiences recognized lines that had been honed by every top banana in the business. Margy and her “client” talk about the gift he is saving for her after a three month absence:

Lt. GREGG Oh, I’ve got something for you, wait until you see this, wait until you see this.

Three Plays by Mae West

Three Plays by Mae West